Iranian and Afghan Taliban forces clashed on the border two weeks ago, resulting in two deaths and several wounded as tensions surrounding water rights continue to rise between Tehran and Kabul.

Each accusing the other of firing first, Iran and Afghanistan are increasingly taking a belligerent stance on the sharing of water supplies as a rapidly changing climate exacerbates water insecurity in the region.

The dispute between the two countries mainly revolves around the Helmand River, whose turquoise waters emerge from the Hindu Kush mountains in east-central Afghanistan and flow southwest across more than half the length of the country before emptying into the Helmand swamps on the border with Iran.

Iran depends heavily on this water for farmland irrigation in the southeastern province of Sistan-Baluchistan, and has recently pointed the finger at Afghanistan for limiting the supply.

Tehran in May accused Kabul of violating a 1973 treaty that grants Iranians the right to use 22 cubic metres of water per second with the possibility of an additional four cubic metres.

Claiming that it is receiving only about 4 percent of the agreed amount, Iran issued a warning to the Taliban and demanded access to Helmand waters.

Dry lake and dust storms

“The Helmand is a river of great importance for Iran because it allows the agricultural areas of Sistan and Baluchestan to develop. And this becomes all the more important as we are in a situation where accelerating sequences of drought and reduced rainfall are putting these agricultural regions at risk,” said Jonathan Piron, a historian specialising in Iran for the Etopia research centre in Brussels.

As a country partly made up of arid and semi-arid land, Iran is increasingly threatened by recent phenomena of desertification as it experiences longer bouts of drought due to climate change.

Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan province is now home to vast expanses of dry land as prolonged droughts have accelerated the shrinking of Lake Hamoun – fed by the Helmand River – which used to be at the heart of the world’s seventh-largest wetlands.

Around the lake, wildlife and vegetation, agriculture and livestock, as well as villages have disappeared, leaving behind a desolate landscape.

To make things worse, the region is turning into a major source of dust storms due to the drop in vegetation cover.

“These dust storms, when they arrive on dry, poor soil, scrape the land even more, raising even more dust, sand and salt, and damaging the good agricultural areas a little further away,” said Piron, who has been conducting water research in Iran for several years.

Afghanistan’s new dams

Water is also a precious commodity in Afghanistan as it is essential to crop cultivation in a country that is threatened by food insecurity.

“There is a desire on the part of the Taliban to regain control of Helmand and to promote water redistribution for their own population in order to assert their legitimacy as rulers,” said Piron.

During the past decades of war that ravaged the country, Afghanistan’s hydraulic infrastructures were neglected, which “favoured the Iranians” despite Afghans’ own water needs.

The former Afghan government accused Tehran of encouraging instability in regions surrounding Afghan dams by supporting armed groups, so that the water could continue to flow beyond the border.

Afghanistan has nevertheless decided to regain control of its hydraulic potential in recent years by speeding up the construction of hydroelectric dams and irrigation systems.

The Kamal Khan Dam, which is situated on the border with Iran, was inaugurated in March 2021 on the Helmand River after six decades of construction work.

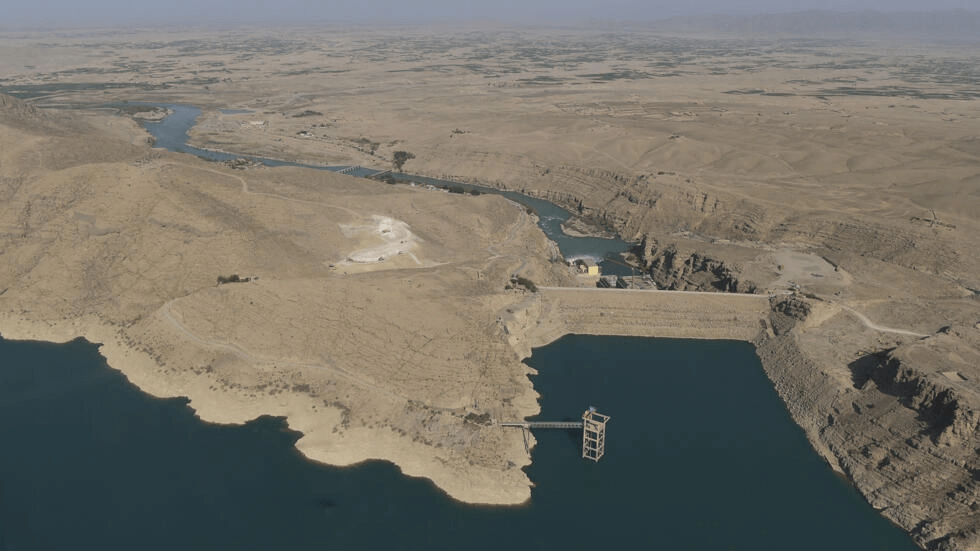

In the meantime, the Kajaki Dam, often a bone of contention with Tehran, has also undergone major work and was recently completed.

Originally built in the 1950s, the dam was abandoned in 1979 during the Soviet invasion. It was only after the fall of the Taliban in 2001 that the US got it running again, after a major overhaul that was eventually scaled back. Later, the Afghan government took charge of new construction work in 2013 after calling in a Turkish company to the rescue.